Land-use applications are a rich source of conflict, almost everywhere.

That’s certainly my experience, here in Victoria. Too often, the interests of developers, public administrators and community members are in conflict, especially when a rezoning, or amendment to the Official Community Plan, is required.

That’s certainly my experience, here in Victoria. Too often, the interests of developers, public administrators and community members are in conflict, especially when a rezoning, or amendment to the Official Community Plan, is required.

It’s not uncommon for changes proposed by a developer to be viewed with suspicion by community members, trust between parties to be minimal, and supporting civic process insufficient to deal with the complexity of land-use decision-making required. And, that’s even with our (Victoria) decent land-use application process, as I wrote about, here.

When land-use conversations become challenging, i.e., conflicted, people tend to glob on to the negative sentiment. It’s not a fair fight for our attention. We are wired to our negativity bias.

What can be done to address those challenges, build consensus among the stakeholder groups, and deescalate conflict?

Major sources of conflict (that I’ve observed and/or experienced directly) during the land-use application process

- The process, especially as it relates to pre-application dialogue, is insufficient for dealing with complex land-use applications and decision-making – too often, land-use development is not treated as a collaborative problem-solving exercise, involving all stakeholders; authentic intent and dialogue (on all sides) is missing from the get-go – as a result, conflicts quickly escalate, and predictably, become intractable, and underlying interests go unattended

- Poor relationship and level of trust between stakeholder groups; e.g., community and developers, especially in those cases where a pre-existing positive relationship doesn’t exist between the two – is a land-use application a stand-alone transaction or is it part of a long-term positive relationship, between all parties, before, during, and after the development?

- Not all community interests are represented; e.g., in my neighbourhood, 67% of residents are renters – they are rarely present at local community meetings – where those present tend to be a few established property owners, and of an older demographic

- Uneven negotiation playing field – land-use applications are essentially a protracted negotiation involving parties: the developer, community (residents and businesses), and the city – the community is the least able to negotiate as a team, with one voice – the community are usually represented by volunteers, including the community’s land-use committee members – the developer and city have paid staff and access to professionals

- Lack of clarity and shared understanding re: application approval process; if clarity means explaining (even complicated) things in simple terms, the current process is not effectively communicated, leading (not surprisingly) to misunderstandings and conflict; proactive communication and education around the land-use application process is largely absent

- Community plans are not up-to-date and/or out-of-sync with current thinking; the land-use application game is often taking place on a moving field; paradoxically, many participants in the land-use application process are uncomfortable with uncertainty and change

3 Mutual-benefit strategies for reducing conflict and improving the land-use application process

- Supplement the pre-application stage of the land-use application process with a Situation Assessment.

The Assessment would be conducted by a third-party neutral; e.g., impartial facilitator or mediator. (My Mayor, Lisa Helps, has also advocated for use of a neutral) The Assessment would be convened by the City, and involves confidential interviews with each stakeholder group. (Non-attributable) stakeholder perspectives are gathered. Information is shared. A summary findings and recommendations reporting takes place. The Assessment can be tailored to match the scope and complexity of the application. The Assessment can also be used (especially on complex applications) to determine if a more comprehensive mutual gains approach is warranted.

(The mutual gains approach would supplement existing process. A mutual gains approach can shift people from an adversarial, decision-making process to a creative information-sharing process focused on the underlying needs and interests of the stakeholders. The mutual gains mutual gains approach is not a single process or technique. It draws from the fields of negotiation, consensus building, collaborative problem solving, alternative dispute resolution, public participation, public administration, and deliberative democracy.)

- Enhance the community’s capacity to constructively negotiate.

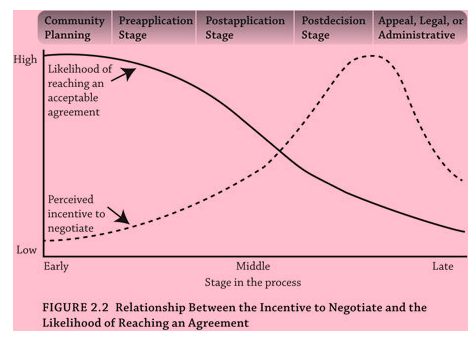

The land-use application process is a negotiation. In my view, the community needs to be better equipped for that negotiation. To level the negotiation playing field, the City should provide additional resources and/or training support for community members involved in the negotiation, of the land-use application. A stronger community negotiation team, evidenced by clear, inclusive and consistent communications, is to everyone’s benefit. The sooner all stakeholders are incentivized and effectively equipped to negotiate, the better, as shown in this graph from, Consensus Building Institute’s book, Land in Conflict: Managing and Resolving Land-Use Disputes.

- Conduct education and training in the collaborative problem-solving and mutual gains approach.

People can’t read minds. And, they aren’t born collaborators. Communication and collaboration, especially of the authentic variety, must be learned. And, once learned, applied, proactively. Land-use partners (e.g., City and industry association, Urban Development Institute) should work together to expand awareness and build skills capacity, at all levels. Healthier relationships and common ground solutions will follow.

Three big questions we need to collectively answer

In any negotiation that I’ve been a part of (as a mediator, I’ve literally facilitated hundreds of negotiations), there are three questions that every participant in the negotiation needs to ask:

- How do we want to work together? (process)

- What will we talk about? (content/issues)

- What sort of relationship do we want with each other? (this question speaks to our emotions, and should never be ignored)

Positive responses to those questions will take you far, together.

[Ben Ziegler is a workplace consultant and mediator, and co-chair of his neighbourhood land-use committee. He is based in Victoria. Contact Ben.]

Speak Your Mind