Last weekend, I spent some time conversing with a few folks in “Tent City”, an encampment of homeless people that has formed on a park-oriented parcel of Crown land, here in Victoria. Tent City is adjacent to the Provincial Court House; a sad irony, if one speaks of social justice. Below is a picture of the two.

The Issues in Context

There are about 100 people in Tent City. They each have their own individual story. Some common themes are apparent; little or no money, job, and/or assets. Mental health is a challenge for many. A sense of community abounds. Such, that people have started constructing their own “homes”, within Tent City. The issues get compounded.

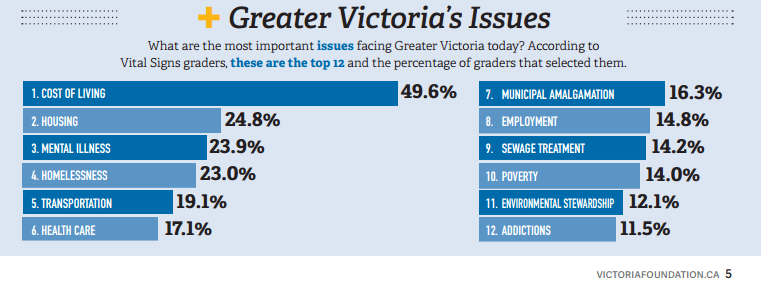

Each year the Victoria Foundation’s Vital Signs report rates the most important issues facing our region. 2015’s looked like this:

Issues intersect. Then, a few local numbers to add some detail:

- $725/month – average cost of bachelor apartment

- 367 – estimated number of chronically hard to home (via Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness)

- $30 million – amount the Capital Regional Hospital District is willing to borrow to house the 367 (if Province contributes similar amount)

- $10.25 – minimum wage

- $20.05 – living wage

- Half a million, plus – cost of average house

Poverty is a complex problem. Inequality predominates. Heck, 65 billiionaires own the same wealth as half the world!

The Poverty Challenge

I’ll take my cue from John Barros, Chief of Economic Development, Boston (@johnfbarros on Twitter): “It takes a job to get out of poverty, but it takes assets to keep you out of poverty.”

I view the challenge as this: If you are poor, it can feel like you are on the bank of a river. Across the river is a better life. Yet, you have nothing to cross that river with.

On one side of the river: no job and no assets. On the other side: job and assets.

Just as stepping stones help you cross a small stream, bigger stepping stones provide bridges across the river of poverty.

Stepping stones

With my mediation and fairness lens on, and in the spirit of collaboration, here are three stepping stones I suggest every leader needs, when it comes to leading poverty reduction:

1. Show you care

Recently, I was in conversation with a small business person in my neighbourhood. He was railing, cynical, about the “homeless” in Tent City. I asked him – Have you been down there, to Tent City? Have you talked to any of the people, there? Do you know their stories? No. No. No. He was operating from stereotype and fear.

The best way to learn people’s stories is to go to them. Be with them. Listen to them. It helps remove the disconnect that often comes with building complex systems.

Our Place Society listened to the stories of people in Tent City. Working with the City of Victoria and other agencies, they helped set up “My Place”, a novel solution for 40 Tent City people. It’s a creative step; helping people transition; through stability and access to support resources.

2. Work together

People want to be treated as partners. It doesn’t matter if you’re homeless or a patient in a hospital (TK).

The headline in The Tyee, a local online newspaper, dated January 12, read: We are part of the solution. It quoted Tent City people, saying they’ll stay (camping) until the provincial government works with them on long-term solutions to the housing crisis.

When it comes to solving complex problems, it takes a system to change a system.

The collaborative leaders’ attitude should be, “we can handle anything, as long as we are together”.

3. Offer a continuum of options

This is the place we get to solutions. In my work as a mediator, and having facilitated ten different virtual project teams, working on innovation challenges, one lesson I learned, the hard way, is first diverge, then converge. To solve a difficult challenge, come up with as many solution ideas as possible. Then “murder your darlings”. Converge on the best ideas.

This should also apply to helping homeless people find a home (a shelter is not a home), and later on, helping poor people acquire assets. Provide a continuum of options.

Two shining options that I recently came across:

First; I discovered L’abri en Ville, a housing program in Quebec. (Thanks to Marg Rose, of the United Way of Greater Victoria for the link). They are a nonprofit who provide long-term housing, e.g., apartments, that include social supports for people living with a mental illness. It is community working together, for individuals capable of living independently with the help of volunteer navigators. There is no program like this, where I live.

Second; architecture’s highest prize is called the Pritzker Prize, it’s basically the Nobel prize of architecture. The 2016 winner, announced two weeks ago, was Chile’s Alejandro Aravena, a man little know known outside his field. He won the award for using architecture as a tool to fight poverty.

Aravena’s houses (2,00o to-date, in Chile and Mexico) are “half a good house”, so called incremental housing, built at low-cost. Half of the basics provided through public funding; the other half to be filled in and completed by the owners as and when they can. The result is that people can remain close to city centres, jobs and resources while living in their own homes, and instead of standardized, high-rise projects (often, poverty ghettos), these customized homes can gain value with sweat equity.

Here’s a good PBS news video about Aravena’s work:

“Because in the end, a housing policy shouldn’t be a mere shelter against the environment. it should work as a tool to overcome poverty.”

Onwards!

Speak Your Mind