The science of friendship.

Work, and life, is more rewarding when it happens with friends. Reflecting back on my four decades (and counting) in the workforce, many of my most treasured work memories are time spent with co-workers who were also friends. We didn’t start out as friends. It happened organically, over time. Whether over coffee breaks, lunch hour games of pick-up basketball, after work hangouts… time spent socializing together led to a mutual feeling of friendship.

When my collaborators were friends, trust was assured, work seemed more enjoyable, and getting things done became easier (and for the most part, done better). Friendships catalyze collaboration, collective impact, and sustainability.

When my collaborators were friends, trust was assured, work seemed more enjoyable, and getting things done became easier (and for the most part, done better). Friendships catalyze collaboration, collective impact, and sustainability.

“When friendships occur, caring follows, and with caring comes a commitment to the long term.” ~ Darren O’Donnell (Haircuts by Children and Other Evidence for a New Social Contract)

Making friends is a time commitment

In community collaborations, in which diverse organizations intentionally come together, typically on a project basis, to get things done, making friends can be a challenge. Partner organizations and community members often don’t know each other, before coming together.

Friendships take time. In a time boxed community collaboration, a hit-and-miss approach to friendship may not be enough. An intentional approach is required.

(My) Logic for how community collaboration and friendship connect

Logical connections:

- Community collaborations succeed through long-term, positive relationships that involve cooperation between the community members.

- “Friendship is a long-term, positive relationship that involves cooperation.” (evolutionary biologists definition)

- Friendship between community members increases the chance of a successful collaboration. Collaboration and Chance are the dynamic duo.

- Making friends requires time spent together, socializing.

- Community collaborations should be structured in ways that provide socializing opportunities for their community members.

Even if all the benefits of friendship won’t be fully realized on your project, it pays to work on those friendships. You never know where they will lead. There is future value in increased collaboration, and friendship.

Three Ways to facilitate the making of friendships in your community collaboration

Intentionality is required. According to neuroscientist, Lisa Feldman Barrett, “You are not born with a social brain, you grow one.”

So how do we become more intentional about making friends? Building on recent research around the science of friendship, here are three pathways to consider exploring:

- Discover what you and your collaborators / partners share in common

- Create opportunities to socialize

- Work with gender differences

Discover what we share in common

We naturally gravitate to people who are similar to us. Get to know the people you are working with. Discover what we have in common. A friendship may follow.

Through his research, evolutionary anthropologist and psychologist Dr. Robin Dunbar (Oxford University) identified 7 pillars of friendship. Some (or all) of these things we may we share in common:

- Language

- Location where grew up

- Educational trajectory (e.g., formal, informal…, a lot, a little)

- Interests and hobbies

- World view (morals, religion, etc.)

- Humour

- Music

Some of these, e.g., language, location, are obvious. Surprisingly, Dunbar’s research showed music to be a powerful connector, especially between strangers. This makes sense. “Music is the shorthand of emotion. Emotions which let themselves be described in words with such difficulty, are directly conveyed… in music, and in that is its power and significance.” (Leo Tolstoy) A potential friend first resonates with us on an emotional front; triggers our endorphins.

Dunbar is also well known for (his) Dunbar’s Number – the maximum number (150) of genuine friends our brain can handle.

Make time for socializing in your collaboration

“Wishing to be friends is quick work, but friendship is a slow ripening fruit.” – Aristotle

Yes, friendships take time. Still, we can accelerate their development by intentionally making time in our collaboration, for socializing. This begs the question – how many hours of socializing does it take to make a friend?

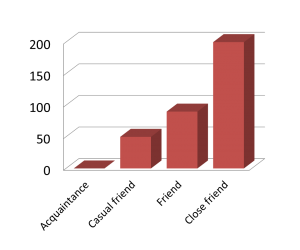

In the first study of its kind, and building on Dunbar’s work, Jeffrey Hall, University of Kansas professor, defined the amount of time necessary to make a friend (excluding romantic friends) as well as how long it typically takes to move through the deepening stages of friendship.

Hall found that it takes roughly 40-60 hours of time together to move from mere “acquaintance” to “casual” friend, 80-100 hours to go from acquaintance to simple “friend” status, and more than 200 hours before you can consider someone your “close” friend.

“This means time spent hanging out, joking around, playing video games and the like. Hours spent working together just don’t count as much.”, Hall’s study found.

“This means time spent hanging out, joking around, playing video games and the like. Hours spent working together just don’t count as much.”, Hall’s study found.

Hall created a nifty web-based Interactive Friendship Tool to probabilistically assess what level of friendship you and another have. Give it a go.

Respect gender differences

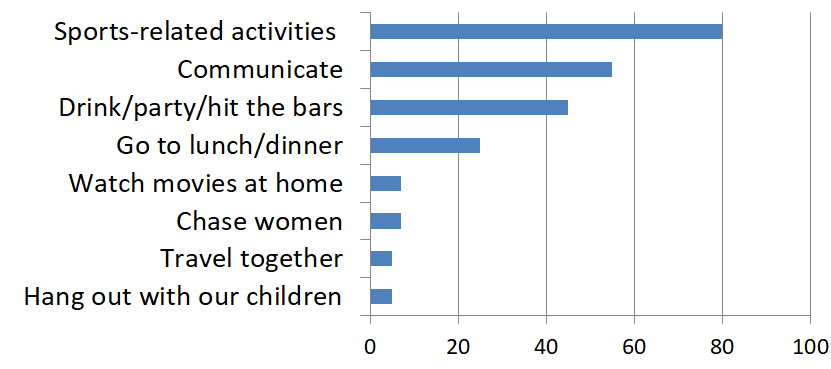

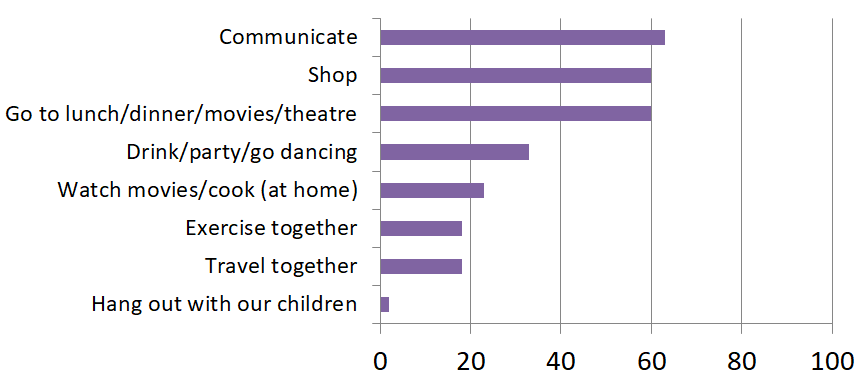

In the Buddy System: Understanding Male Friendships, which I read to inform me for a men’s support group that I facilitate, professor Dr. Geoffrey Grief, and his research team, interviewed 400 men, and 140 women. His insights, on what men do together (with other men), and what women do together (with other women):

What do men do, together? (%’s)

What do women do, together? (%’s)

So what? Well, I think one can apply these gender insights, to community collaboration. What socializing activities might bridge the gender divide (if there is one in your collaboration)?

You can also apply Greif’s research to training. In a workplace training capacity, I sometimes intentionally use a sports metaphor as a training activity, to ensure the men in the room are fully engaged.

Apply the science of friendship to your next project

Maybe a local United Way, or other funding agency, has recently awarded your community collaboration a grant? How will you apply the science of friendship?

Why not commit to developing friendships in your community collaboration?